Python JSON Log Limits: What Are They and How Can You Avoid Them?

Python JSON logging has become the standard for generating readable structured data from logs. While monitoring logs in JSON is definitely much better than using the…

Python is a highly skilled language with a large developer community, which is essential in data science, machine learning, embedded applications, and back-end web and cloud applications.

And logging is critical to understanding software behavior in Python. Once logs are in place, log monitoring can be utilized to make sense of what is happening in the software. Python includes several logging libraries that create and direct logs to their assigned targets.

This article will go over Python logging best practices to help you get the best log monitoring setup for your organization.

we’ll be in touch shortly.

Logging in Python, like other programming languages, is implemented to indicate events that have occurred in software. Logs should include descriptive messages and variable data to communicate the state of the software at the time of logging.

They also communicate the severity of the event using unique log levels. Logs can be generated using the Python standard library.

The Python standard library provides a logging module to log events from applications and libraries. Once the Python JSON logger is configured, it becomes part of the Python interpreter process that is running the code.

In other words, Python logging is global. You can also configure the Python logging subsystem using an external configuration file. The specifications for the logging configuration format are found in the Python standard library documentation.

The logging library is modular and offers four categories of components:

Multiple logger objects are organized into a tree representing various parts of your system and the different third-party libraries you have installed. When you send a message to one of the loggers, the message gets output on that logger’s handlers using a formatter attached to each handler.

The message then propagates the logger tree until it hits the root logger or a logger in the tree configured with .propagate=False. This hierarchy allows logs to be captured up the subtree of loggers, and a single handler could catch all logging messages.

The logging.Logger objects offer the primary interface to the logging library. These objects provide the logging methods to issue log requests along with the methods to query and modify their state. From here on out, we will refer to Logger objects as loggers.

The factory function logging.getLogger(name) is typically used to create loggers. By using the factory function, clients can rely on the library to manage loggers and access loggers via their names instead of storing and passing references to loggers.

The name argument in the factory function is typically a dot-separated hierarchical name, i.e. a.b.c. This naming convention enables the library to maintain a hierarchy of loggers. Specifically, when the factory function creates a logger, the library ensures a logger exists for each level of the hierarchy specified by the name, and every logger in the hierarchy is linked to its parent and child loggers.

Each logger has a threshold logging level to determine whether a log request should be processed. A logger processes a log request if the numeric value of the requested logging level is greater than or equal to the severity of the logger’s threshold logging level.

Clients can retrieve and change the threshold logging level of a logger via Logger.getEffectiveLevel() and Logger.setLevel(level) methods, respectively. When the factory function is used to create a logger, the function sets a logger’s threshold logging level to the threshold logging level of its parent logger as determined by its name.

Log levels allow you to define event severity for each log so they are easily analyzed. Python supports predefined values, which can be found by calling logging.getLevelName(). Predefined log levels include CRITICAL, ERROR, WARNING, INFO, and DEBUG from highest to lowest severity. Developers can also maintain a dictionary of log levels by defining custom levels using logging.getLogger().

LogWithLevelName = logging.getLogger(‘myLoggerSample’) level = logging.getLevelName(‘INFO’) LogWithLevelName.setLevel(level)

Python comes with different methods to read events from the software: print() and logging. Both will communicate event data but pass this information to different storage locations using different methods.

The print function sends data exclusively to the console. This can be convenient for fast testing as a function is developed, but it is not practical for use in functional software. There are two critical reasons to not use print() in software:

The logging library also provides many features contributing to Python logging best practices. These include identifying the line of the file, function, and time of log events, distinguishing log events by their importance, and providing formatting to keep log messages consistent.

Here are a few code snippets to illustrate how to use the Python logging library.

# main.py

import logging, sys

def _init_logger(): #Create a logger named 'app'

logger = logging.getLogger('app')

#Set the threshold logging level of the logger to INFO

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

#Create a stream-based handler that writes the log entries #into the standard output stream

handler = logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout)

#Create a formatter for the logs

formatter = logging.Formatter( '%(created)f:%(levelname)s:%(name)s:%(module)s:%(message)s')

#Set the created formatter as the formatter of the handler handler.setFormatter(formatter)

#Add the created handler to this logger

logger.addHandler(handler)

_init_logger()

_logger = logging.getLogger('app')

In snippet 1, a logger is created with a log level of INFO. Any logs that have a severity less than INFO will not print (i.e. DEBUG logs). A new handler is created and assigned to the logger. New handlers can be added to send logging outputs to streams like sys.stdout or any file-like object.

A formatter is created and added to the handler to transform log messages into placeholder data. In this formatter, the time of the log request (as an epoch timestamp), the logging level, the logger’s name, the module name, and the log message will all print.

# main.py

_logger.info('App started in %s', os.getcwd())

In snippet 2, an info log states the app has started. When the app is started in the folder /home/kali with the logger created in snippet 1, the following log entry will be generated in the std.out stream:

1586147623.484407:INFO:app:main:App started in /home/kali/

# app/io.py

import logging

def _init_logger():

logger = logging.getLogger('app.io')

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

_init_logger()

_logger = logging.getLogger('app.io')

def write_data(file_name, data):

try:

# write data

_logger.info('Successfully wrote %d bytes into %s', len(data), file_name)

except FileNotFoundError:

_logger.exception('Failed to write data into %s', file_name)

This snippet logs an informational message every time data is written successfully via write_data. If a write fails, the snippet logs an error message that includes the stack trace in which the exception occurred. The logs here use positional arguments to enhance the value of the logs and provide more contextual information.

With the logger created using snippet 1, successful execution of write_data would create a log similar to:

1586149091.005398:INFO:app.io:io:Successfully wrote 134 bytes into /tmp/tmp_data.txt

If the execution fails, then the created log will appear like:

1586149219.893821:ERROR:app:io:Failed to write data into /tmp1/tmp_data.txt

Traceback (most recent call last):

File “/home/kali/program/app/io.py”, line 12, in write_data

print(open(file_name), data)

FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘/tmp1/tmp_data.txt’

Alternatively to positional arguments, the same outputs could be achieved using complete names as in:

_logger.info('Successfully wrote %(data_size)s bytes into %(file_name)s',

{'data_size': len(data), 'file_name': file_name})

Every logger offers a shorthand method to log requests by level. Each pre-defined log level is available in shorthand; for example, Logger.error(msg, *args, **kwargs).

In addition to these shorthand methods, loggers also offer a general method to specify the log level in the arguments. This method is useful when using custom logging levels.

Logger.log(level, msg, *args, **kwargs)

Another useful method is used for logs inside exception handlers. It issues log requests with the logging level ERROR and captures the current exception as part of the log entry.

Logger.exception(msg, *args, **kwargs)

In each of the methods above, the msg and args arguments are combined to create log messages captured by log entries. They each support the keyword argument exc_info to add exception information to log entries and stack_info and stacklevel to add call stack information to log entries. Also, they support the keyword argument extra, which is a dictionary, to pass values relevant to filters, handlers, and formatters.

To get the most out of your Python logging, they need to be set up consistently and ready to analyze. When setting up your Python logging, use these best practices below.

The logging.getLogger() factory function helps the library manage the mapping from logger names to logger instances and maintain a hierarchy of loggers. In turn, this mapping and hierarchy offer the following benefits:

Use the shorthand logging.<logging level>() method to log at pre-defined logging levels. Besides making the code a bit shorter, the use of these functions helps partition the logging statements into two sets:

The pre-defined logging levels capture almost all logging scenarios that occur. Most developers are universally familiar with these logging levels across different programming languages, making them easy to understand. The use of these values reduces deployment, configuration, and maintenance burdens.

While creating loggers, we can create a logger for each class or create a logger for each module. While the first option enables fine-grained configuration, it leads to more loggers in a program, i.e., one per class. In contrast, the second option can help reduce the number of loggers in a program. So, unless such fine-grained configuration is necessary, create module-level loggers.

Use logging.LoggerAdapter() to inject contextual information into log records. The class can also modify the log message and data provided as part of the request. Since the logging library does not manage these adapters, they cannot be accessed with common names. Use them to inject contextual information local to a module or class.

Two options exist to seamlessly inject global contextual information (common across an app) into log records. The first option is to use the filter support to modify the log record arguments provided to filters. For example, the following filter injects version information into incoming log records.

def version_injecting_filter(logRecord): logRecord.version = '3' return True

There are two downsides to this option. First, if filters depend on the data in log records, then filters that inject data into log records should be executed before filters that use the injected data. Thus, the order of filters added to loggers and handlers becomes crucial. Second, the option “abuses” the support to filter log records to extend log records.

The second option is to initialize the logging library with a log record creating a factory function via logging.setLogRecordFactory(). Since the injected contextual information is global, it can be injected into log records when created in the factory function. This ensures the data will be available to every filter, formatter, logger, and handler in the program.

The downside of this option is that we have to ensure factory functions contributed by different components in a program play nicely with each other. While log record factory functions could be chained, such chaining increases the complexity of programs.

A logger will process a log request based on the effective logging level. The effective logging level is the higher of two logging levels: the logger’s threshold level and the library-wide level. Set the library-wide logging level using the logging.disable(level) function. This is set to 0 by default so that every log request will be processed.

Using this function, the software will throttle the logging output of an app by increasing the logging level across the whole app. This can be important to keep log volumes in check in production software.

Python’s logging library is more complicated than simple print() statements. The library has many great features that provide a complete solution for obtaining log data needed to achieve full-stack observability in your software.

Here we show the high-level advantages and disadvantages of the library.

The Python logging library is highly configurable. Logs can be formatted before printing, can have placeholder data filled in automatically, and can be turned on and off as needed. Logs can also be sent to a number of different locations for easier reading and debugging. All of these settings are codified, so are well-defined for each logger.

In failures, it is useful to log debugging information showing where and when a failure occurred. These tracebacks can be generated automatically in the Python logging library to help speed up troubleshooting and fixes.

Log levels used in different scenarios can be subjective across a development team. For proper analysis, it is important to keep log levels consistent. Create a well-defined strategy for your team about when to use each logging level available and when a custom level is appropriate.

Since the logging module is so flexible, logging configurations can quickly get complicated. Create a strategy for your team for how each logging module will be defined to keep logs consistent across developers.

Let’s look at an example of a basic logger in Python:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG,

format='%(asctime)s %(levelname)s %(message)s',

filename='/tmp/myapp.log',

filemode='w')

logging.debug("Debug message")

logging.info("Informative message")

logging.error("Error message")

Line 1: import the logging module.

Line 2: create a basicConf function and pass some arguments to create the log file. In this case, we indicate the severity level, date format, filename and file mode to have the function overwrite the log file.

Line 3 to 5: messages for each logging level.

The default format for log records is SEVERITY: LOGGER: MESSAGE. Hence, if you run the code above as is, you’ll get this output:

2021-07-02 13:00:08,743 DEBUG Debug message 2021-07-02 13:00:08,743 INFO Informative message 2021-07-02 13:00:08,743 ERROR Error message

Regarding the output, you can set the destination of the log messages. As a first step, you can print messages to the screen using this sample code:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG, format='%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

logging.debug('This is a log message.')

If your goals are aimed at the Cloud, you can take advantage of Python’s set of logging handlers to redirect content. Currently in beta release, you can write logs to Stackdriver Logging from Python applications by using Google’s Python logging handler included with the Stackdriver Logging client library, or by using the client library to access the API directly. When developing your logger, take into account that the root logger doesn’t use your log handler. Since the Python Client for Stackdriver Logging library also does logging, you may get a recursive loop if the root logger uses your Python log handler.

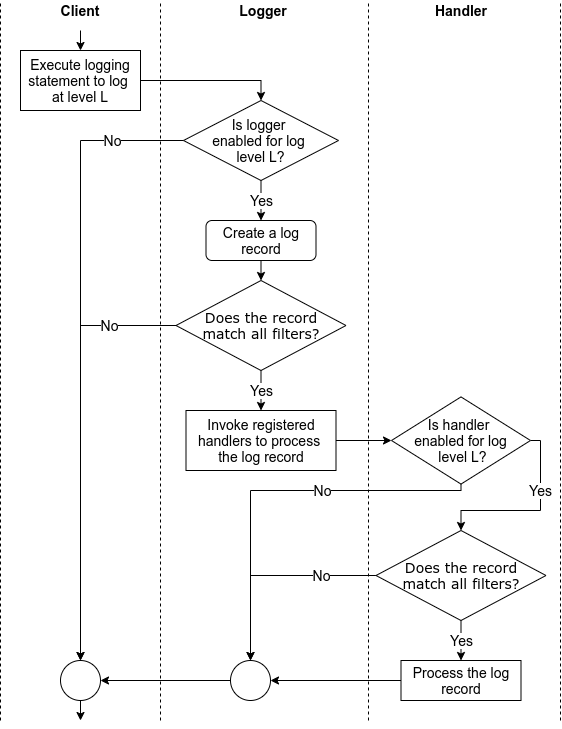

When we use a logging library, we perform/trigger the following common tasks while using the associated concepts (highlighted in bold).

Independent of the logging library, the above tasks are performed in an order similar to that shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The flow of tasks when logging via a logging library

Every logger offers the following logging methods to issue log requests.

Logger.critical(msg, *args, **kwargs)Logger.error(msg, *args, **kwargs)Logger.debug(msg, *args, **kwargs)Logger.info(msg, *args, **kwargs)Logger.warn(msg, *args, **kwargs)Each of these methods is a shorthand to issue log requests with corresponding pre-defined logging levels as the requested logging level.

In addition to the above methods, loggers also offer the following two methods:

Logger.log(level, msg, *args, **kwargs) issues log requests with explicitly specified logging levels. This method is useful when using custom logging levels.Logger.exception(msg, *args, **kwargs) issues log requests with the logging level ERROR and that capture the current exception as part of the log entries. Consequently, clients should invoke this method only from an exception handler.msg and args arguments in the above methods are combined to create log messages captured by log entries. All of the above methods support the keyword argument exc_info to add exception information to log entries and stack_info and stacklevel to add call stack information to log entries. Also, they support the keyword argument extra, which is a dictionary, to pass values relevant to filters, handlers, and formatters.

When executed, the above methods perform/trigger all of the tasks shown in Figure 1 and the following two tasks:

LogRecord object to represent the log request in the downstream processing of the request. LogRecord objects capture the msg and args arguments of logging methods and the exception and call stack information along with source code information. They also capture the keys and values in the extra argument of the logging method as fields.Logger.propagate field controls this aspect, which is True by default.Beyond logging levels, filters provide a finer means to filter log requests based on the information in a log record, e.g., ignore log requests issued in a specific class. Clients can add and remove filters to/from loggers using Logger.addFilter(filter) and Logger.removeFilter(filter) methods, respectively.

The logging classes introduced in the previous section provide methods to configure their instances and, consequently, customize the use of the logging library. Snippet 1 demonstrates how to use configuration methods. These methods are best used in simple single-file programs.

When involved programs (e.g., apps, libraries) use the logging library, a better option is to externalize the configuration of the logging library. Such externalization allows users to customize certain facets of logging in a program (e.g., specify the location of log files, use custom loggers/handlers/formatters/filters) and, hence, ease the deployment and use of the program. We refer to this approach to configuration as data-based approach.

Clients can configure the logging library by invoking logging.config.dictConfig(config: Dict) function. The config argument is a dictionary and the following optional keys can be used to specify a configuration.

filters key maps to a dictionary of strings and dictionaries. The strings serve as filter ids used to refer to filters in the configuration (e.g., adding a filter to a logger) while the mapped dictionaries serve as filter configurations. The string value of the name key in filter configurations is used to construct logging.Filter instances.

"filters": {

"io_filter": {

"name": "app.io"

}

}

This configuration snippet results in the creation of a filter that admits all records created by the logger named ‘app.io’ or its descendants.

formatters key maps to a dictionary of strings and dictionaries. The strings serve as formatter ids used to refer to formatters in the configuration (e.g., adding a formatter to a handler) while the mapped dictionaries serve as formatter configurations. The string values of the datefmt and format keys in formatter configurations are used as the date and log entry formatting strings, respectively, to construct logging.Formatter instances. The boolean value of the (optional) validate key controls the validation of the format strings during the construction of a formatter.

"formatters": {

"simple": {

"format": "%(asctime)s - %(message)s",

"datefmt": "%y%j-%H%M%S"

},

"detailed": {

"format": "%(asctime)s - %(pathname):%(lineno) - %(message)s"

}

}

This configuration snippet results in the creation of two formatters. A simple formatter with the specified log entry and date formatting strings and detailed formatter with specified log entry formatting string and default date formatting string.

handlers key maps to a dictionary of strings and dictionaries. The strings serve as handler ids used to refer to handlers in the configuration (e.g., adding a handler to a logger) while the mapped dictionaries serve as handler configurations. The string value of the class key in a handler configuration names the class to instantiate to construct a handler. The string value of the (optional) level key specifies the logging level of the instantiated handler. The string value of the (optional) formatter key specifies the id of the formatter of the handler. Likewise, the list of values of the (optional) filters key specifies the ids of the filters of the handler. The remaining keys are passed as keyword arguments to the handler’s constructor.

"handlers": {

"stderr": {

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"level": "INFO",

"filters": ["io_filter"],

"formatter": "simple",

"stream": "ext://sys.stderr"

},

"alert": {

"class": "logging.handlers.SMTPHandler",

"level": "ERROR",

"formatter": "detailed",

"mailhost": "smtp.skynet.com",

"fromaddr": "[email protected]",

"toaddrs": [ "[email protected]", "[email protected]" ],

"subject": "System Alert"

}

}

This configuration snippet results in the creation of two handlers:

stderr handler that formats log requests with INFO and higher logging level log via the simple formatter and emits the resulting log entry into the standard error stream. The stream key is passed as keyword arguments to logging.StreamHandler constructor.stream key illustrates how to access objects external to the configuration. The ext:// prefixed string refers to the object that is accessible when the string without the ext:// prefix (i.e., sys.stderr) is processed via the normal importing mechanism. Refer to Access to external objects for more details. Refer to Access to internal objects for details about a similar mechanism based on cfg:// prefix to refer to objects internal to a configuration.detailed formatter and emails the resulting log entry to the given email addresses. The keys mailhost, formaddr, toaddrs, and subject are passed as keyword arguments to logging.handlers.SMTPHandler’s constructor.loggers key maps to a dictionary of strings that serve as logger names and dictionaries that serve as logger configurations. The string value of the (optional) level key specifies the logging level of the logger. The boolean value of the (optional) propagate key specifies the propagation setting of the logger. The list of values of the (optional) filters key specifies the ids of the filters of the logger. Likewise, the list of values of the (optional) handlers key specifies the ids of the handlers of the logger.

"loggers": {

"app": {

"handlers": ["stderr", "alert"],

"level": "WARNING"

},

"app.io": {

"level": "INFO"

}

}

This configuration snippet results in the creation of two loggers. The first logger is named app, its threshold logging level is set to WARNING, and it is configured to forward log requests to stderr and alert handlers. The second logger is named app.io, and its threshold logging level is set to INFO. Since a log request is propagated to the handlers associated with every ascendant logger, every log request with INFO or a higher logging level made via the app.io logger will be propagated to and handled by both stderr and alert handlers.

root key maps to a dictionary of configuration for the root logger. The format of the mapped dictionary is the same as the mapped dictionary for a logger.

incremental key maps to either True or False (default). If True, then only logging levels and propagate options of loggers, handlers, and root loggers are processed, and all other bits of the configuration is ignored. This key is useful to alter existing logging configuration. Refer to Incremental Configuration for more details.

disable_existing_loggers key maps to either True (default) or False. If False, then all existing non-root loggers are disabled as a result of processing this configuration.

Also, the config argument should map the version key to 1.

Here’s the complete configuration composed of the above snippets.

{

"version": 1,

"filters": {

"io_filter": {

"name": "app.io"

}

},

"formatters": {

"simple": {

"format": "%(asctime)s - %(message)s",

"datefmt": "%y%j-%H%M%S"

},

"detailed": {

"format": "%(asctime)s - %(pathname):%(lineno) - %(message)s"

}

},

"handlers": {

"stderr": {

"class": "logging.StreamHandler",

"level": "INFO",

"filters": ["io_filter"],

"formatter": "simple",

"stream": "ext://sys.stderr"

},

"alert": {

"class": "logging.handlers.SMTPHandler",

"level": "ERROR",

"formatter": "detailed",

"mailhost": "smtp.skynet.com",

"fromaddr": "[email protected]",

"toaddrs": [ "[email protected]", "[email protected]" ],

"subject": "System Alert"

}

},

"loggers": {

"app": {

"handlers": ["stderr", "alert"],

"level": "WARNING"

},

"app.io": {

"level": "INFO"

}

}

}

The configuration schema for filters supports a pattern to specify a factory function to create a filter. In this pattern, a filter configuration maps the () key to the fully qualified name of a filter creating factory function along with a set of keys and values to be passed as keyword arguments to the factory function. In addition, attributes and values can be added to custom filters by mapping the . key to a dictionary of attribute names and values.

For example, the below configuration will cause the invocation of app.logging.customFilterFactory(startTime='6PM', endTime='6AM') to create a custom filter and the addition of local attribute with the value True to this filter.

"filters": {

"time_filter": {

"()": "app.logging.create_custom_factory",

"startTime": "6PM",

"endTime": "6PM",

".": {

"local": true

}

}

}

Configuration schemas for formatters, handlers, and loggers also support the above pattern. In the case of handlers/loggers, if this pattern and the class key occur in the configuration dictionary, then this pattern is used to create handlers/loggers. Refer to User-defined Objects for more details.

The logging library also supports loading configuration from a configparser-format file via the <a href="https://docs.python.org/3/library/logging.config.html#logging.config.fileConfig" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">logging.config.fileConfig() function. Since this is an older API that does not provide all of the functionalities offered by the dictionary-based configuration scheme, the use of the dictConfig() function is recommended; hence, we’re not discussing the fileConfig() function and the configparser file format in this tutorial.

While the above APIs can be used to update the logging configuration when the client is running (e.g., web services), programming such update mechanisms from scratch can be cumbersome. The logging.config.listen() function alleviates this issue. This function starts a socket server that accepts new configurations over the wire and loads them via dictConfig() or fileConfig() functions. Refer to logging.config.listen() for more details.

Since the configuration provided to dictConfig() is nothing but a collection of nested dictionaries, a logging configuration can be easily represented in JSON and YAML format. Consequently, programs can use the json module in Python’s standard library or external YAML processing libraries to read and write logging configurations from files.

For example, the following snippet suffices to load the logging configuration stored in JSON format.

import json, logging.config

with open('logging-config.json', 'rt') as f:

config = json.load(f)

logging.config.dictConfig(config)

In the supported configuration scheme, we cannot configure filters to filter beyond simple name-based filtering. For example, we cannot create a filter that admits only log requests created between 6 PM and 6 AM. We need to program such filters in Python and add them to loggers and handlers via factory functions or the addFilter() method.

We’ll be in touch shortly.

While logging statements help capture information at locations in a program, they contribute to the cost of the program in terms of execution time (logging statements in loops) and storage (logging lots of data). Although cost-free yet useful logging is impossible, we can reduce the cost of logging by making choices that are informed by performance considerations.

After adding logging statements to a program, we can use the support to configure logging (described earlier) to control the execution of logging statements and the associated execution time. In particular, consider the following configuration capabilities when making decisions about logging-related performance.

The above changes the range over coarser to finer aspects of logging support in Python.

While the support to configure logging is powerful, it cannot help control the performance impact of implementation choices baked into the source code. Here are a few such logging-related implementation choices and the reasons why you should consider them when making decisions about logging-related performance.

Upon adding the logging module to Python’s standard library, there were concerns about the execution cost associated with inactive logging statements — logging statements that issue log requests with logging level lower than the threshold logging level of the target logger. For example, how much extra time will a logging statement that invokes logger.debug(...) add to a program’s execution time when the threshold logging level of logger is logging.WARN? This concern led to client-side coding patterns (as shown below) that used the threshold logging level of the target logger to control the execution of the logging statement.

# client code

...

if logger.isEnabledFor(logging.DEBUG):

logger.debug(msg)

...

Today, this concern is not valid because the logging methods in the logging.Logger class perform similar checks and process the log requests only if the checks pass. For example, as shown below, the above check is performed in the logging.Logger.debug method.

# client code

...

logger.debug(msg)

...

# logging library code

class Logger:

...

def debug(self, msg, *args, **kwargs):

if self.isEnabledFor(DEBUG):

self._log(DEBUG, msg, args, **kwargs)

Consequently, inactive logging statements effectively turn into no-op statements and do not contribute to the execution cost of the program.

Even so, one should consider the following two aspects when adding logging statements.

logger.debug(...) when threshold logging level of logger was logging.WARN took half a second on a typical laptop. So, while the cost of an inactive logging statement is trivial, the total execution cost of numerous inactive logging statements can quickly add up to be non-trivial.Clients can construct log messages in two ways: eagerly and lazily.

logging method, e.g., logger.debug(f'Entering method Foo: {x=}, {y=}').f-strings and the format() method, but it involves the eager construction of log messages, i.e., before the logging statements are deemed as active.printf-style message format string (as a msg argument) and the values (as a args argument) to construct the log message to the logging method, e.g., logger.debug('Entering method %s: x=%d, y=%f', 'Foo', x, y). After the logging statement is deemed as active, the logger constructs the log message using the string formatting operator %.While both approaches result in the same outcome, they exhibit different performance characteristics due to the eagerness and laziness of message construction.

For example, on a typical laptop, a million inactive invocations of logger.debug('Test message {0}'.format(t)) takes 2197ms while a million inactive invocations of logger.debug('Test message %s', t) takes 1111ms when t is a list of four integers. In the case of a million active invocations, the first approach takes 11061ms and the second approach took 10149ms. A savings of 9–50% of the time taken for logging!

So, the second (lazy) approach is more performant than the first (eager) approach in cases of both inactive and active logging statements. Further, the gains would be larger when the message construction is non-trivial, e.g., use of many arguments, conversion of complex arguments to strings.

By default, when a log record is created, the following data is captured in the log record:

Unless these bits of data are logged, gathering them unnecessarily increases the execution cost. So, if these bits of data will not be logged, then configure the logging framework to not gather them by setting the following flags.

logging.logProcesses = Falselogging.logThreads = Falselogging.logMultiProcessing = Falselogging._srcFile = NoneThere are situations where we may want to log data in the main thread of execution without spending almost any time logging the data. Such situations are common in web services, e.g., a request processing thread needs to log incoming web requests without significantly increasing its response time. We can tackle these situations by separating concerns across threads: a client/main thread creates a log record while a logging thread logs the record. Since the task of logging is often slower as it involves slower resources (e.g., secondary storage) or other services (e.g., logging services such as Coralogix, pub-sub systems such as Kafka), this separation of concerns helps minimize the effort of logging on the execution time of the main/client thread.

The Python logging library helps handle such situations via the QueueHandler and QueueListener classes as follows.

QueueHandler and QueueListener instances are initialized with a queue.QueueHandler instance receives a log record from the client, it merely places the log request in its queue while executing in the client’s thread. Given the simplicity of the task performed by the QueueHandler, the client thread hardly pauses.QueueListener queue, the listener retrieves the log record and executes the handlers registered with the listener to handle the log record. In terms of execution, the listener and the registered handlers execute in a dedicated thread that is different from the client thread.Note: While QueueListener comes with a default threading strategy, developers are not required to use this strategy to use QueueHandler. Instead, developers can use alternative threading strategies that meet their needs.

That about wraps it up for this Python logging guide. If you’re looking for a log management solution to centralize your Python logs, check out our easy-to-configure Python integration.